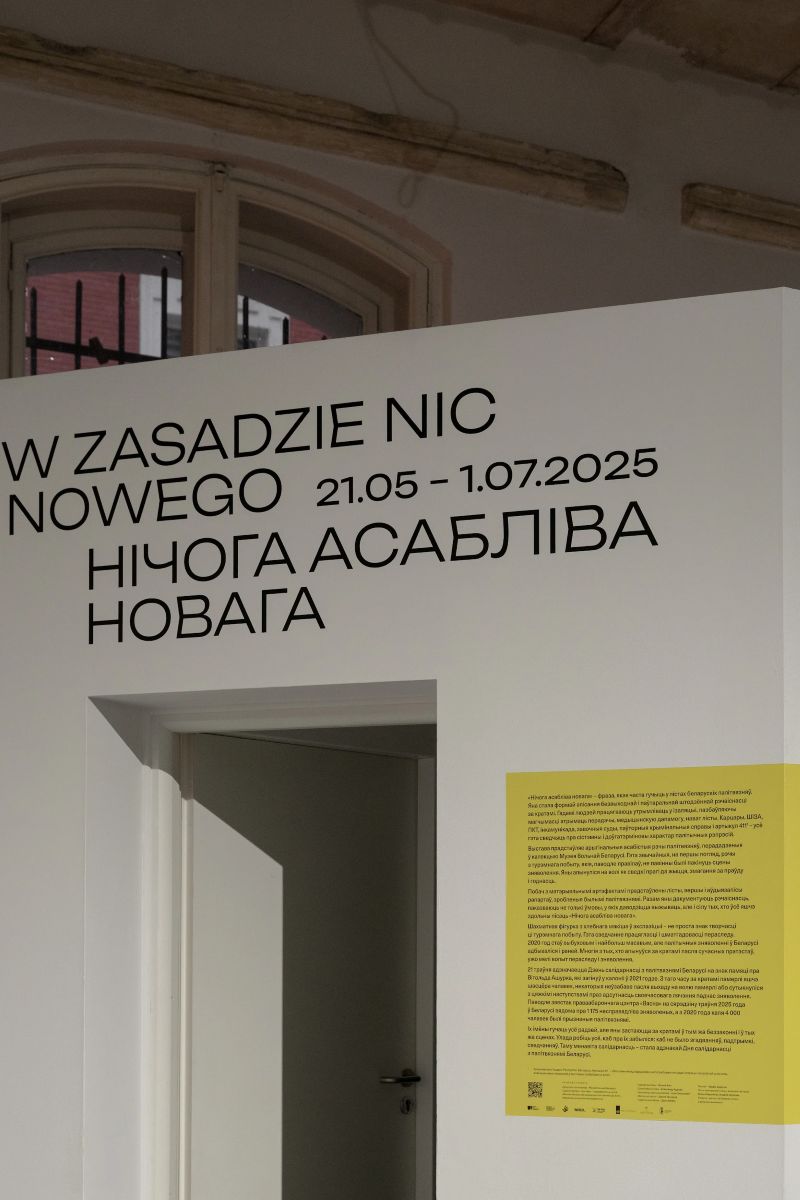

At the Museum of Free Belarus in Warsaw (11 Foksal Street), the exhibition “Nothing Particularly New” has opened, dedicated to the everyday life of Belarusian political prisoners.

Our contributor Liza Mas spoke with the creators of the exhibition and reflected on the meanings behind this complex display.

The phrase “Nothing Particularly New” was deliberately chosen as the exhibition’s title. These exact words often appear in letters from Belarusian political prisoners to their families and friends. Behind this restrained expression of daily life lie the dramatic circumstances of imprisonment — a way for the incarcerated to comfort their loved ones while concealing pain, fear, and the monotony of confinement. In essence, it is an irony of fate: for someone behind bars, “nothing new” means reliving the same experience of unfreedom day after day.

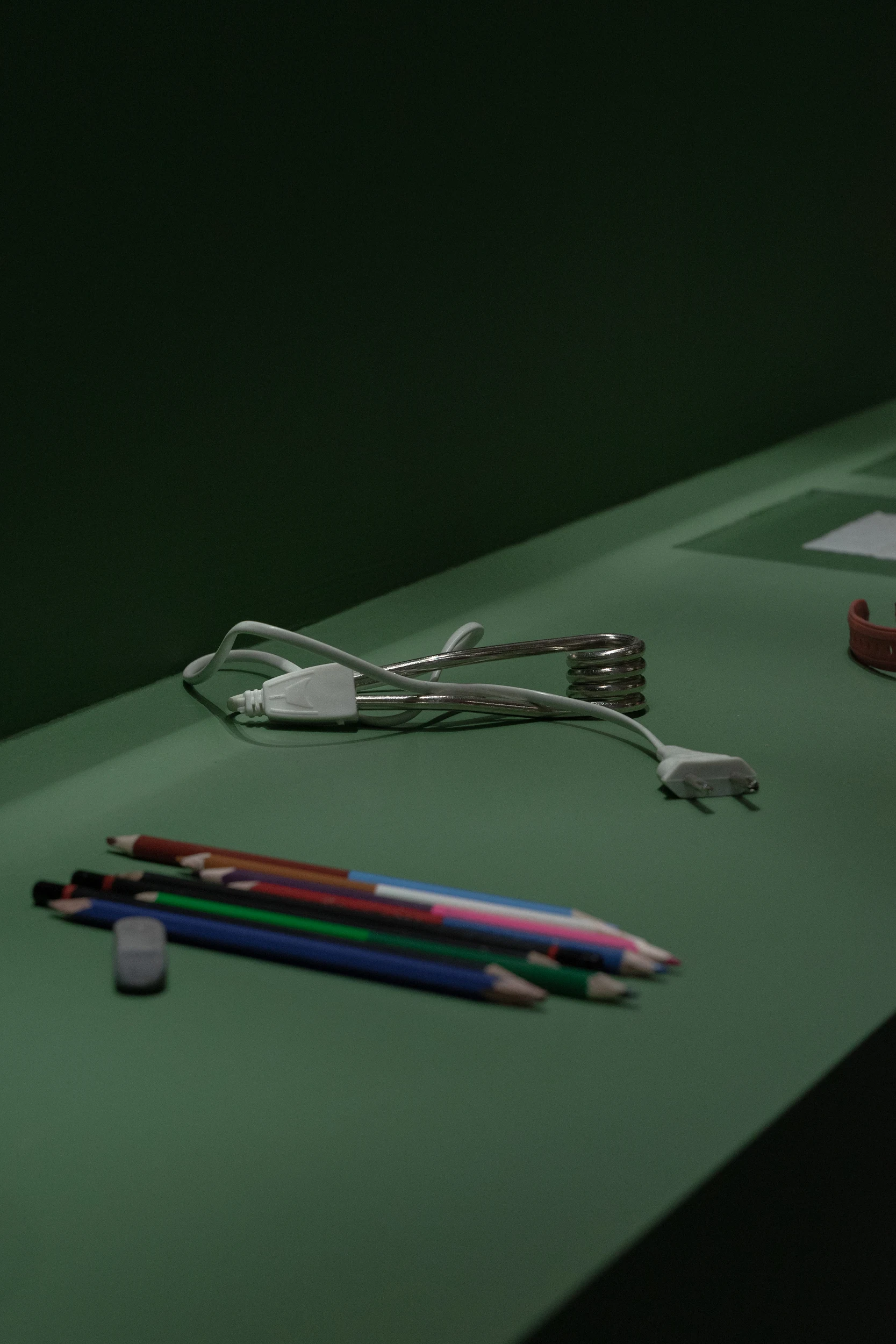

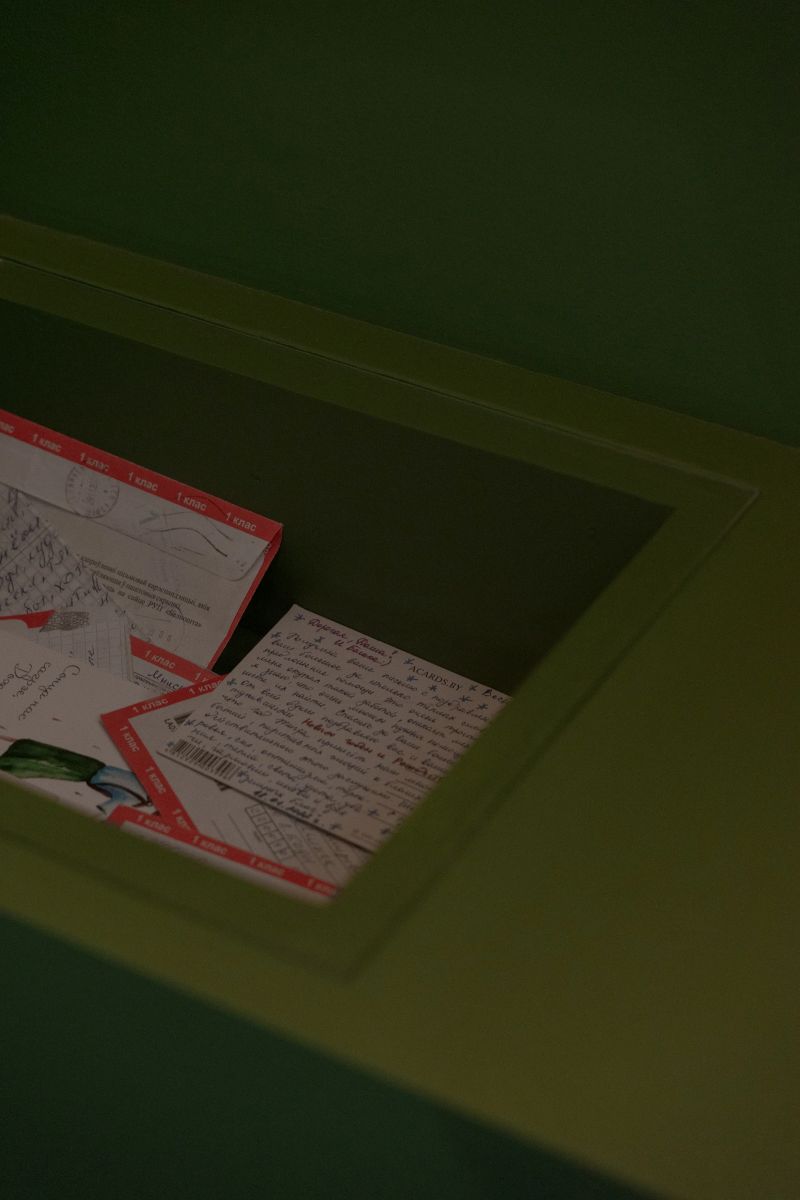

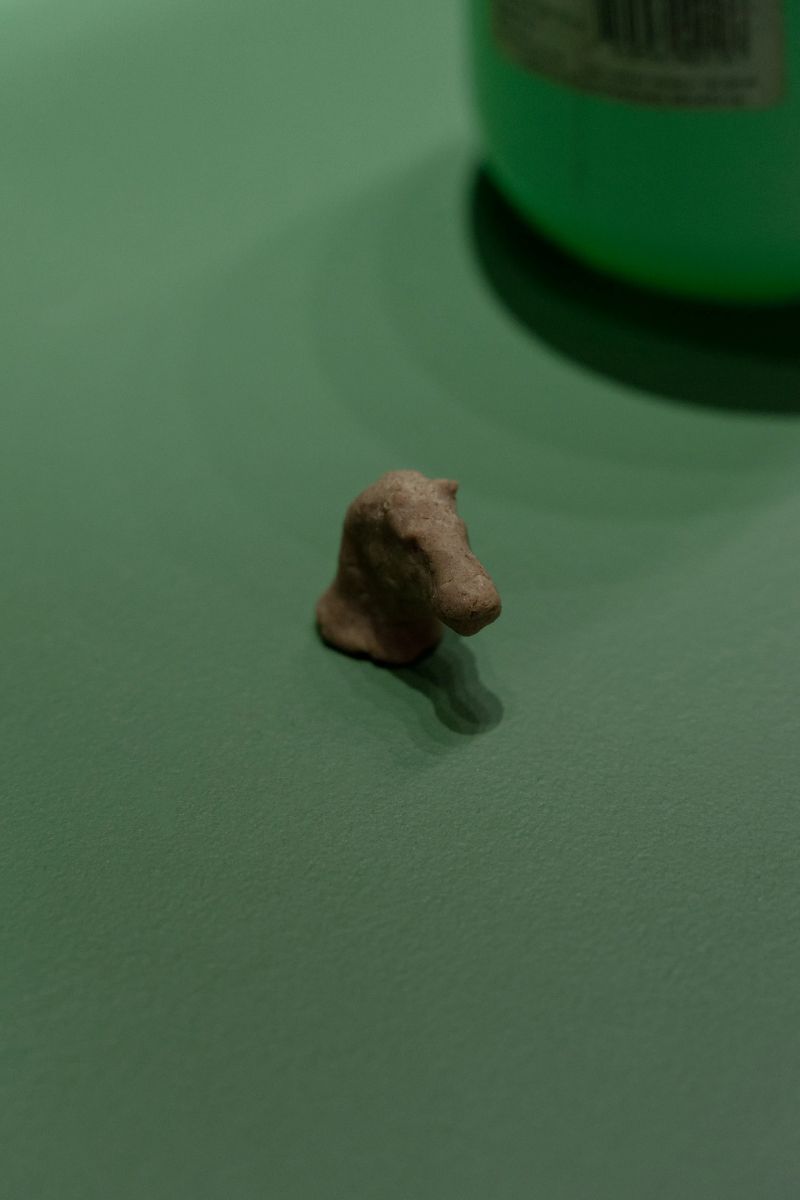

The exhibition is housed in a small room of the Museum of Free Belarus, designed to evoke the atmosphere of a prison cell. Large windows with metal bars instantly recall the reality of confinement. The lighting is soft and subdued — a mixture of daylight filtered through the bars and focused spotlights highlighting the exhibits. On the shelves are small everyday objects: pencils, plastic cups, notes, drawings made in prison, a chess piece displayed under glass, and official documents. Prison clothing hangs separately — ghostlike — on a special installation designed by Belarusian artist Aliaksandr Adamau.

Project curator Volha Klip notes:

“This is an art exhibition based on real events. The artifacts on display are authentic — there aren’t many of them, and they are so ordinary that without understanding the context, it’s hard to grasp their historical significance. That’s why the work of the artists who created the immersive space played a crucial role: the goal was to convey the inner state of political prisoners. I heard visitors say they got goosebumps.”

The idea for the project came from the Museum of Free Belarus team and was brought to life by curator Volha Klip. The exhibition’s visual design was created by Belarusian artist Aliaksandr Adamau, while the sound design was developed by Ilya Semashkevich.

The walls of the hall are painted in a gray-green color, reminiscent of the typical paint used in government corridors and prison rooms. Notably, only one wall is entirely white — it displays drawings made by a political prisoner.

The white background visually lifts the drawings beyond the confines of the prison cell, giving them an effect of existing in another reality—a space of inner freedom. These are not artifacts from imprisonment, but images that penetrate the confined space from the outside. The subjects of the drawings include illustrations for Alice in Wonderland and One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. One particular colored drawing of daisies evokes an almost childlike sense of peace and hope.

Against the green background, brightly colored objects stand out.

On one of the shelves lies a red-and-white deodorant tube, next to it — blue safety razors. These items are instantly recognizable, yet in the museum context they appear out of place, as if transported from another layer of reality.

Separately displayed is a pink dress that sharply contrasts with the monotone surroundings. Attached to the dress is a yellow tag — marking the status of a “political” prisoner.

According to the Human Rights Center “Viasna”, as of June 3, 2025, there are 1,208 political prisoners in Belarus, around 100 of whom are cultural figures.

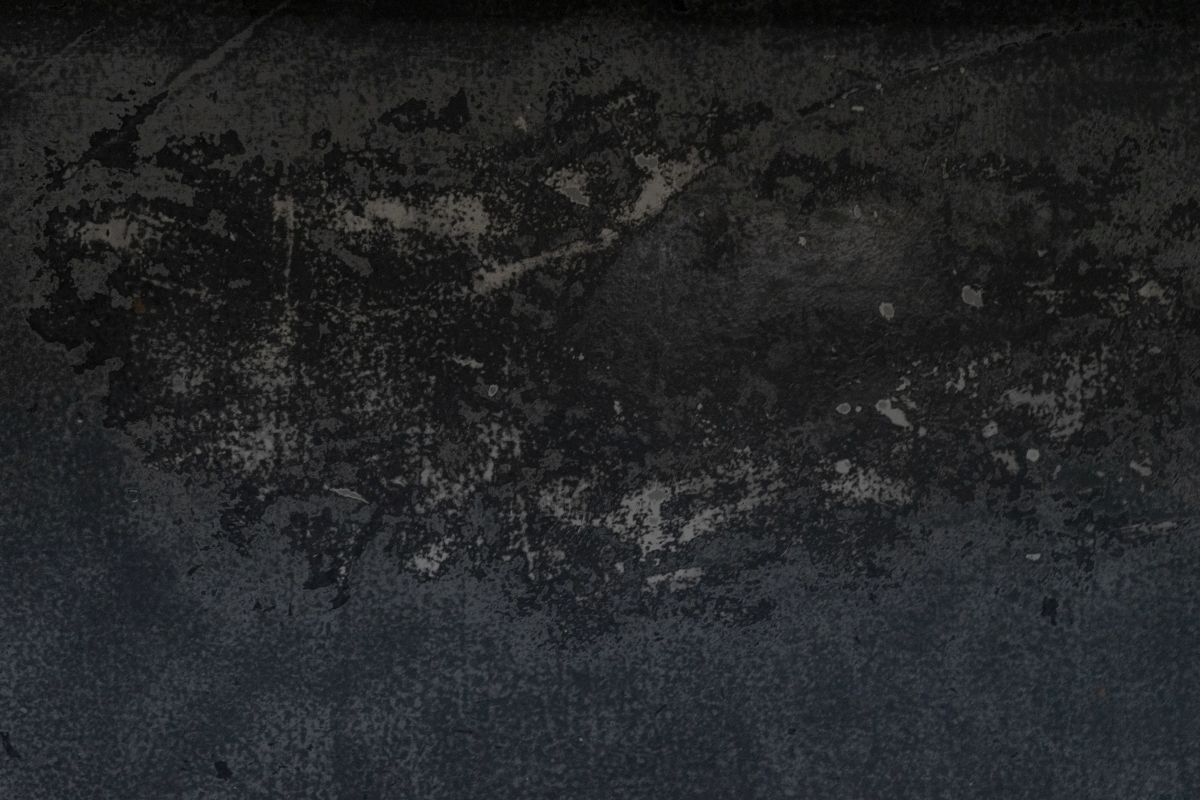

The floor is made of gray concrete. As the exhibition’s curator notes, artist Aliaksandr Adamau intentionally created a worn, scuffed surface in front of certain key exhibits. This artistic choice evokes the feeling of a frequently visited space, suggesting prolonged contemplation — as if people pause here again and again.

“The starting point for finding the visual solution was the artifacts themselves — their everyday nature, recognizability, and quantity,” says Aliaksandr Adamau. “I was especially struck by a simple plastic bag, yellowed and torn on one side — it once held a modest hygiene kit.

Wanting to create a space that focuses attention on each object, I began designing the exhibition. The room itself was quite specific geometrically — narrow, with two cut corners and three tall windows.

To achieve controlled lighting, we covered the windows with a light-absorbing film that blocks about 85 percent of daylight. And to guide and prepare visitors, we built an additional corridor — narrow and low.

Of course, sound became an important element of the exhibition, as it was literally essential to ‘tell the stories.’ Visitors can listen to poetry and fragments of letters.

The surreal and tense atmosphere of the space is enhanced by details: a horizontal mirror reflecting the barred windows and the viewers themselves; a single light bulb hanging over the shelf of letters; and the unevenly worn, gray-dirty floor.”

“In the small room, through the silence, one constantly hears the monotonous hum of political prisoners’ reports. The corridor through which the viewer walks speaks in their words — the daily declarations the prisoners were forced to repeat aloud.

Beyond the wall, this rhythm is picked up by an ambient composition created specifically for the exhibition by the composer, amplifying the sense of confinement and systemic pressure,” explains project curator Volha Klip.

The most powerful part of the exhibition is the words of the prisoners themselves. These are the typical daily reports that political prisoners were forced to recite aloud: “I, [surname], convicted under Article…, prone to extremism…”

Letters read by Belarusian actors Volha Karaliok and Andrej Sauchanka, as well as poems performed by the authors themselves — former political prisoners — are heard throughout the exhibition, amplifying the emotional impact of the physical artifacts.

While the objects tell the story of daily prison life, the words reveal the inner world of those behind bars — their thoughts, emotions, and struggles.

“I’m fine, nothing particularly new…” — this short line from a letter opens a window into life in captivity. Behind its calm tone may hide time spent in solitary confinement, administrative pressure, or health problems.

The exhibition is presented in three languages — Belarusian, English, and Polish. Captions, informational materials, and part of the audio content have been specially adapted for an international audience.

The texts written behind barbed wire are perceived here as documents of an era and testimonies of resistance. Every poem, every letter, is an expression of a freedom of spirit stronger than walls.

The organizers hope that the exhibition will not only tell the story of repression but also strengthen solidarity with political prisoners.

For now, there is still “nothing particularly new” in Belarusian prisons — the days pass, and people remain behind bars. It is our duty, in freedom, to remember them and do everything possible to bring closer the morning when their night of captivity ends.

Financial and organizational support: Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in Warsaw, City of Warsaw, and the Trzy Trąby Foundation.

Co-organizers and partners: Human Rights Center Viasna, Belarusian Association of Political Prisoners Da Voli, and the National Anti-Crisis Management (NAU).

The exhibition “Nothing Particularly New” will be open until July 1.

Original article: reform.news