On March 6–7, the Museum of Free Belarus is hosting a meeting of specialists in museum studies and related fields to discuss the creation of a museum laboratory — an association of professionals, and possibly also enthusiasts, that will bring together Belarusians both in the country and in exile.

According to the Museum’s director, Natallia Zadziarkoŭskaya, the laboratory is envisioned as a community of museum workers, researchers, and cultural experts engaged in preserving cultural heritage and memory. The term “laboratory” reflects the practical orientation of this professional network.

During the discussion, participants noted that students should also be involved, as they can learn from professionals, contribute new ideas, and assist in many aspects. Enthusiasts of museum work could likewise play a valuable role, while broader audience engagement would increase the museum’s visibility and public appeal.

An example was given of the German Historical Museum in Berlin, where civil society took part alongside professionals in shaping the institution’s concept and narratives. Museum laboratories already exist in many countries, often with specialized focuses: the Metropolitan Museum in New York works on media policy, while the Pittsburgh Museum Laboratory develops experimental exhibitions. Some serve as hubs for research and networking.

In this way, the initiative of the Museum of Free Belarus follows a global trend.

One of the missions of museums in exile, as seen by the professional community, is to represent Belarus culturally and to inform the world about it. An example was given of the Goethe Institutes as representatives of Germany abroad, with the phrase “cultural embassy” even being used.

Pavel Shautsou, one of the trustees of the Skaryna Library in London, joined the meeting online. He emphasized the importance of considering the experience of earlier waves of emigration. After World War II, it was much harder to explain Belarus and Ukraine to the free world, as they were often perceived as part of Russia — yet Belarusians succeeded.

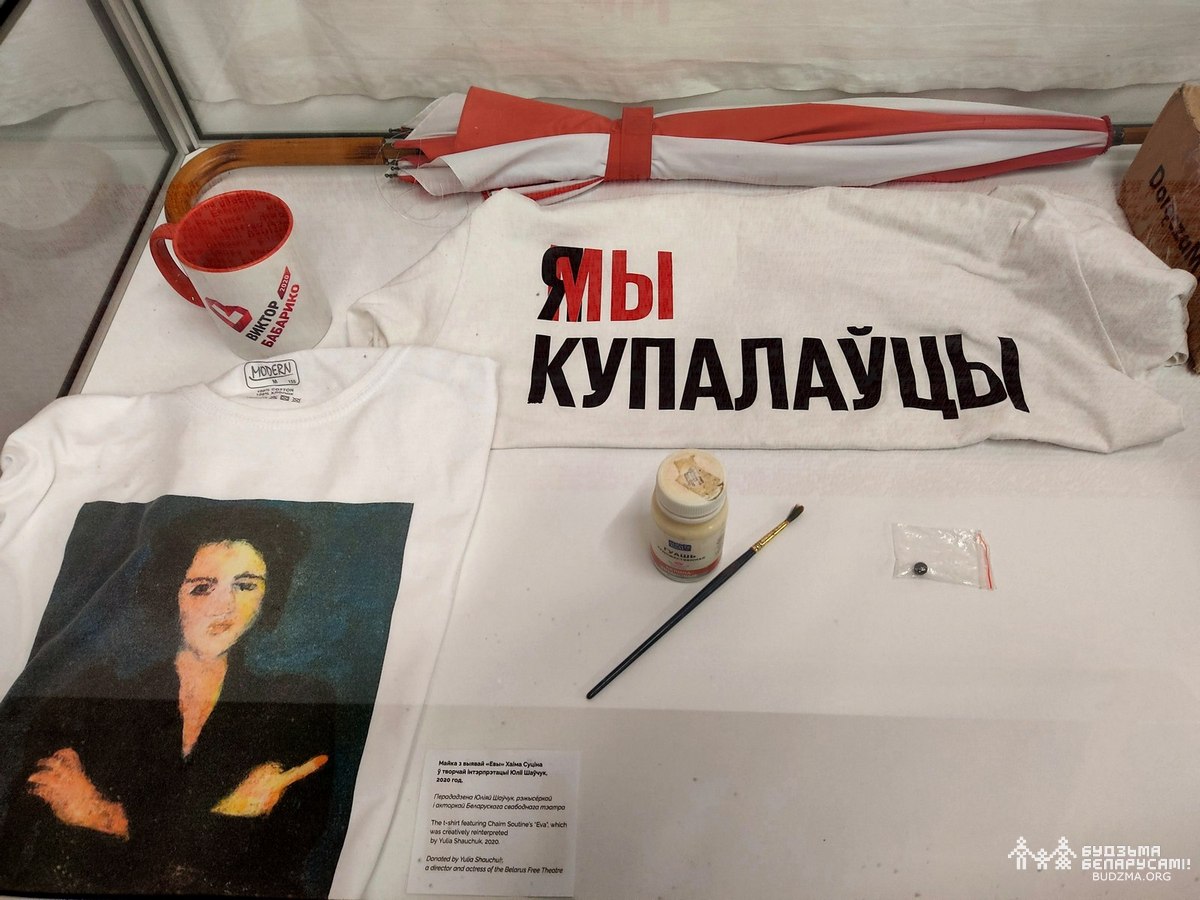

Shautsou believes that Belarusian museums in exile should maintain clear specialization in both their activities and collections: while the Skaryna Library in London focuses on the postwar emigration, the Museum of Free Belarus documents the events of 2020 and beyond.

It was also noted that, unlike the mid-20th-century emigration, today’s wave includes not only enthusiasts but also many professionals. For this reason, most participants see the museum laboratory primarily as a professional association.

However, it should not be limited only to museum workers in exile. “No initiative of Belarusians abroad can be considered complete without the involvement of people inside Belarus,” emphasized Siarhei Budkin, head of the Belarusian Council of Culture. “There is a strong temptation to stay in a bubble — to gather with friends over Czech or Polish beer, come up with an idea, find a grant or sponsor, and quietly implement it. I see this trend growing, and that is why I would very much like to counteract it and remind people that we are working for change in Belarus.”

At the meeting, it was emphasized that the participation of colleagues from Belarus in the work of the museum laboratory will be organized with full respect for all possible security protocols. At the same time, it was acknowledged that some of the projects currently carried out by Belarusians in exile cannot be implemented inside Belarus.

Original article: budzma.org