At the beginning of summer, the Museum of Free Belarus will celebrate its third anniversary. While this is not a long enough period to present a vast collection, it is sufficient to sum up certain results. Recently, the museum also initiated the creation of a museum laboratory aimed at forming an association of specialists who would join efforts on both sides of the border. In addition, it conducted a sociological survey to better understand visitors’ interests and adjust its work accordingly. The survey results, carried out by Vardamatski’s laboratory, may prove useful for all cultural institutions in exile.

We spoke with Natallia Zadziarkoŭskaya, director of the Museum of Free Belarus, about the next stage of the institution’s development and the new challenges facing the emigration community.

— The Belarusian Museum Laboratory you initiated is meant to become a platform for coordination and cooperation among professionals both in Belarus and abroad. Did the idea to hold it come after the sociological survey?

— The survey showed that we need to look not only for a niche for ourselves but also for an audience that matches our specialization. So we proposed to gather and began working to create a museum community in exile.

Such a community could, first, attract resources and give museum professionals here the opportunity to continue their work.

Second, museum workers in Belarus would gain access through us to current museum practices and innovations.

And third, through access to European antique markets, museum collections, and archives, we can care for the preservation of our historical and cultural heritage.

These are our goals. And people from other countries have also joined the laboratory.

We are now preparing documentation and discussing the plan for further actions. I believe a separate cultural initiative for and about museum professionals will emerge, gradually acquiring its own subjectivity.

It is still necessary to resolve issues such as relations with ICOM — the International Council of Museums. For example, how can we represent democratic Belarus within ICOM while being based abroad? There are also questions about potential cooperation with other international organizations and consortia, given that we are not yet formally legalized.

As for contact with Belarusians inside the country, it is essential to establish a secure communication channel with them and carefully work out the details of a safety protocol.

— When you founded the Museum of Free Belarus about three years ago, you must have had a certain concept and plans. How much has the concept changed over this time?

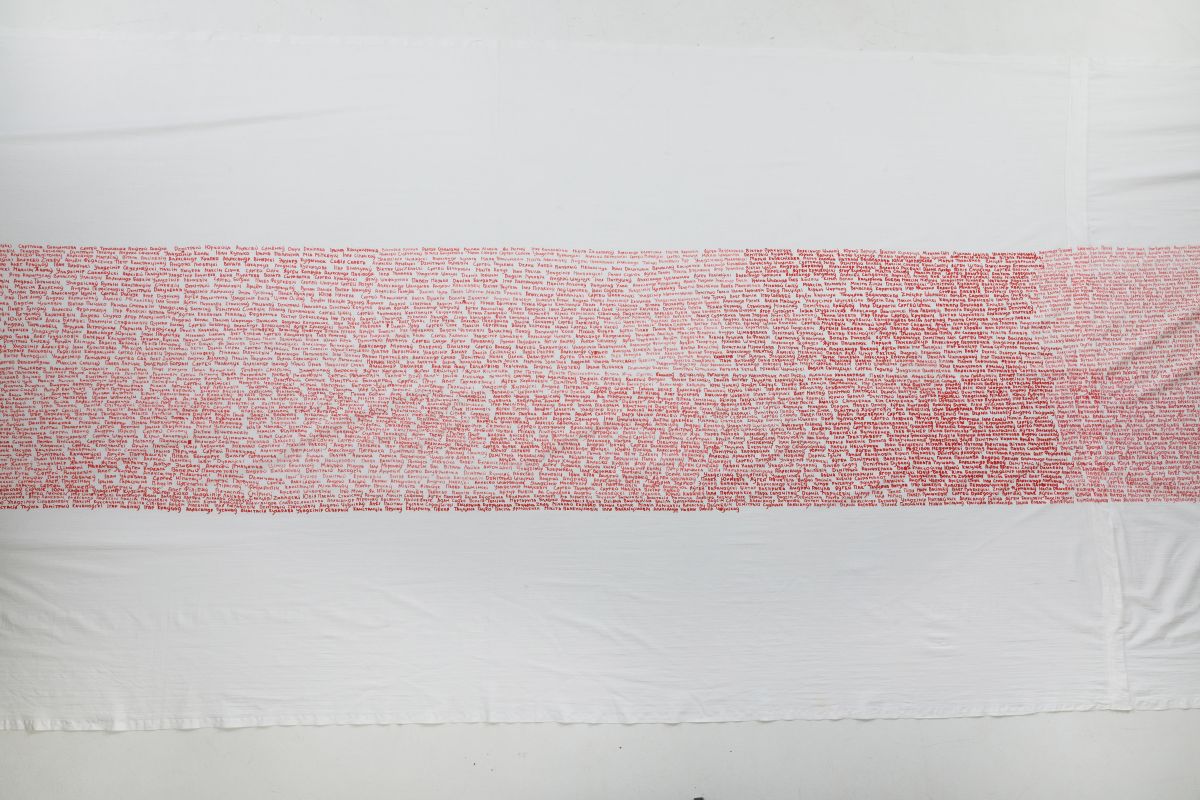

— From the very beginning until today, our strategic mission and main direction have not changed. We created an institution to preserve and museify the Belarusian protest of 2020 and the subsequent period. This part of our work remains, but it is now time to expand the chronological framework, because the events of 2020 did not arise in a vacuum. Many people who joined the protest had previously participated in other forms of the struggle for Belarus’s independence. Some continue this fight today, resisting Russia’s aggression against Ukraine.

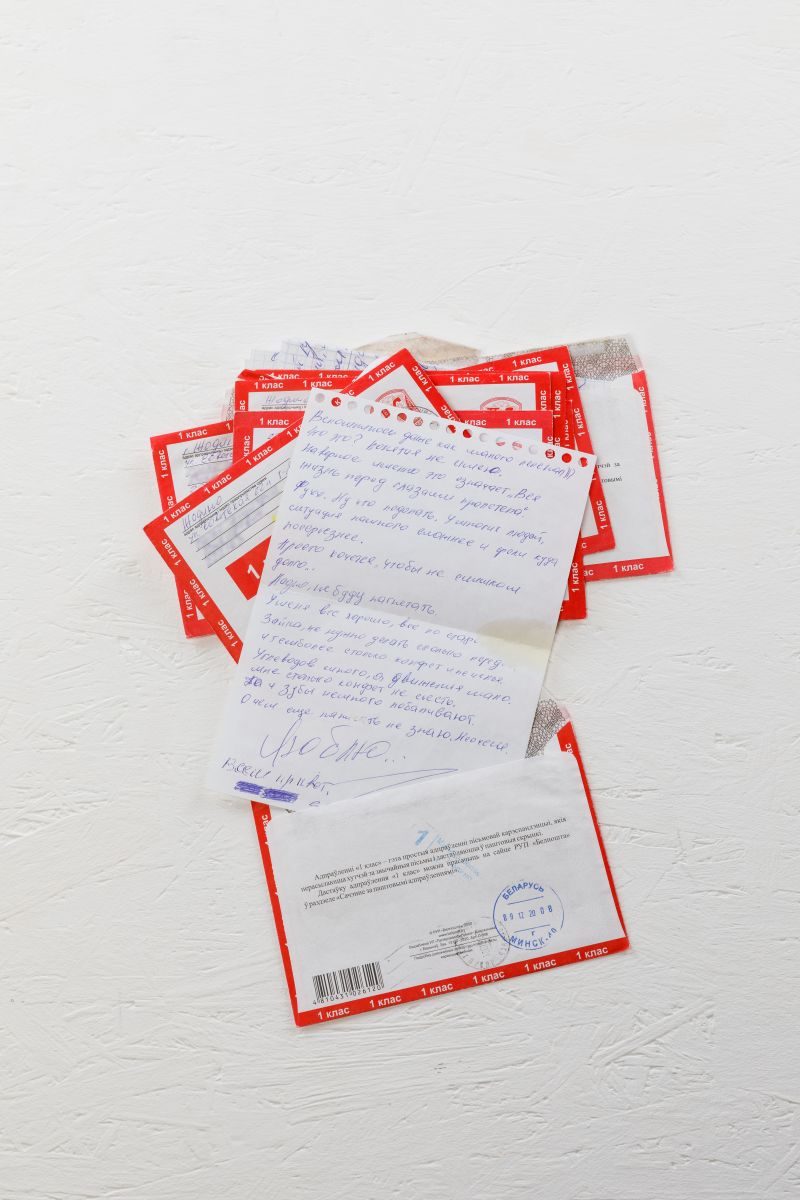

When the museum was founded, its primary mission was to safeguard and rescue objects and artifacts that would otherwise disappear or be deliberately destroyed by the regime.

Now we are working on developing an algorithm that would allow us to save items from Belarus that are under threat of destruction. We still lack resources, but if we manage to create such an algorithm, it will establish a channel for rescuing artifacts — from the simplest steps, such as preserving photos and documents digitally, to saving physical objects. For example, we are currently working with an item that may serve as evidence in the International Criminal Court of crimes against humanity committed during the dispersal of demonstrations.

— I understand that artifacts from 2020 can be taken out of Belarus in a suitcase. But how do you receive items from earlier periods?

— The sources can be very diverse. Until recently, the oldest item we had received dated back to 1996. Now we have obtained a book for our library which is also a museum exhibit, as it originates from the 19th century.

I hope we will have the opportunity to purchase objects at auctions that are connected with the long history of Belarusians’ struggle for freedom — for example, with the Kalinouski Uprising. This is now also part of our profile. Accordingly, the structure of our collection will evolve.

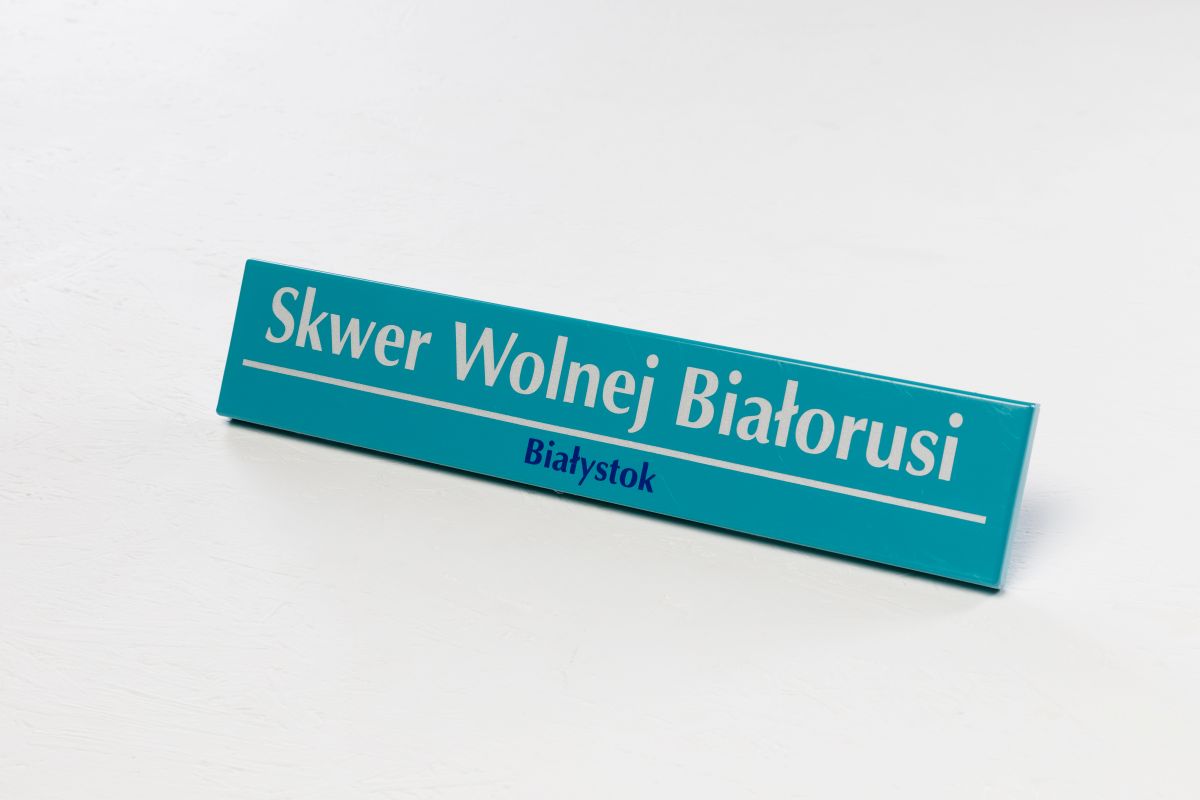

— When you began working in Warsaw, you probably assumed this period would be short. Yet time goes on, and it is necessary to integrate into the Warsaw museum scene. Is the survey you recently conducted connected with the new challenges you face? For example, should you also work for a Polish audience?

— In our work, we must always keep our finger on the pulse, know who we are working with, and understand the direction we need to move. The impulses for development should not lie in the past but must be found in the present.

As a museum, we must preserve the objects that would otherwise disappear. At the same time, we must work with the people living nearby and respond to their needs.

In our survey, we asked for the opinions of both Belarusians and Poles, since we exist within the Polish cultural environment. Poles know very little about Belarusians and show little interest. Yet we are precisely a platform through which people can get to know Belarusians. That is why we are keen to understand Polish interests and remain open to this audience.

There was another reason for including Polish respondents. Today, there is a noticeable outflow of Belarusian artists from Belarusian platforms. Belarusians are doing well — they are integrating. In the early years, for creative self-realization, they turned to Belarusian initiatives, but now they see opportunities in other European institutions. On the one hand, this means they are in demand and becoming full participants in the European artistic process. On the other, it gives us reason to reflect, since competing with European institutions is difficult. So why not invite the Polish public — the very same audience our artists seek outside Belarusian platforms — to our own venues?

We have had Polish projects and Belarusian projects, but they did not intersect. Meanwhile, almost every week we receive foreign guests — Americans, Italians, Spaniards. And we also need to showcase Belarus to them.

— How do people find you?

— Thanks to our presence on Google Maps and on tourist routes in various guides. There are also random visitors who need us to explain what Belarus is. So we become representatives of the whole country.

— What is the status of your institution?

— We are a non-governmental organization. During the laboratory it became clear that all Belarusian institutions engaged in museum activities operate as non-profit organizations. Even the Francis Skaryna Library and Museum in London, founded in the 1950s.

At one point, we received a proposal to become a structural unit of a Polish institution. There are both advantages and disadvantages to this. On the one hand, if we were to face unfavorable financial conditions, how could we ensure the preservation of these items? In that case, finding a legal framework where the Polish state would take responsibility for safeguarding the collection could be a good option.

On the other hand, with the victory of democratic forces, we have always planned to take these objects back to Belarus, where they would be placed in a new Museum of Free Belarus, or become part of the National Historical Museum. But if we legalize ourselves here as a structural unit, given the requirements for preserving museum collections, will there not be procedural obstacles when we want to take them back? The first question that arises is whether we will be free to manage our own collection.

These are important issues for any museum — and a fundamental question for us.

— Did the survey provide answers about the direction to take and what events to organize at the museum?

— Yes, there were many questions related to cultural program demand and what forms attract people more. Some were more interested in exhibitions, others in performances.

I was surprised that many respondents showed a strong interest in discussion formats. It seemed that everything had already been said, yet the need remains. We were also advised to use our outdoor space more actively.

While Belarusians know about Belarusian venues, the Polish audience does not — apart from a few representatives of Polish cultural organizations.

What struck me most was the recommendation from Poles that we should more clearly emphasize that the museum is not connected to the Lukashenka regime. We thought the very name — “Museum of Free Belarus” — already made that clear.

Poles also noted that Belarusian cultural institutions are almost invisible in Poland, especially compared to Ukrainian and Georgian projects, and that there is virtually no coverage in the Polish media. They are interested in Belarusian events, but they don’t receive information about them. When we send out newsletters, people respond; when an important Polish guest is invited, there is no space left for cameras. That is why we want to be more visible.

— Maybe it would be worth organizing more joint projects?

— Yes, including that. Now, when writing project applications, we are making visibility of the museum and its work a priority.

Another important conclusion of the survey is that institutions need to offer their own cultural product that will be relevant not only for Belarusians but also for the society of the host country. It is essential to find our own way of presenting Belarus abroad. This is also a question donors are now considering — whom to support. We must preserve balance for our own community while being open to the outside world.

I believe we need to present our unique cultural products more actively and build friendships and supporters who will advocate for Belarusian culture — because we do have something to show the world. This is my main takeaway.

I was very inspired by the responses of a Polish expert who has worked extensively with Belarusians, the director of the Polish institution Staromiejski Dom Kultury. He stressed that Belarusian platforms are important not only for Belarusians but also for Polish society. He rejected the term “integration” and suggested using “adaptation” instead. He wrote that Belarusians are full participants in Poland’s cultural process, describing them as “educated, proactive, self-reliant, and capable of self-organization.”.

It is inspiring that people believe in us, see our strength and potential, and regard us as equal participants in the cultural process.

Original article: reform.news