The premiere performances of the play My Mother in Prison, based on the book by psychologist Volha Vialichka about the children of political prisoners, took place in Vilnius, Białystok, and Warsaw. The final performance was held on February 22 at the Museum of Free Belarus.

Psychologist Volha Vialichka has been working with the children of political prisoners for several years. This was a new experience for her, as she initially had little understanding of how to work with children whose parents were taken away, beaten, or subjected to home searches right before their eyes. In search of answers, she began studying a new field for herself—penitentiary psychology—and examined the experiences of former prisoners of German and Soviet concentration camps. These were the memories of already grown-up individuals, yet Vialichka found many parallels.

In her book From 2 to 15: My Mother in Prison, which she began writing unexpectedly for herself, she included the stories of Soviet children from the Akmolinsk camp for wives of traitors to the Motherland, forming one of the final sections of the book. Director Natallia Liavanova opened the play with these harrowing scenes and then, without pause, turned to the fears and dreams of the children of contemporary political prisoners.

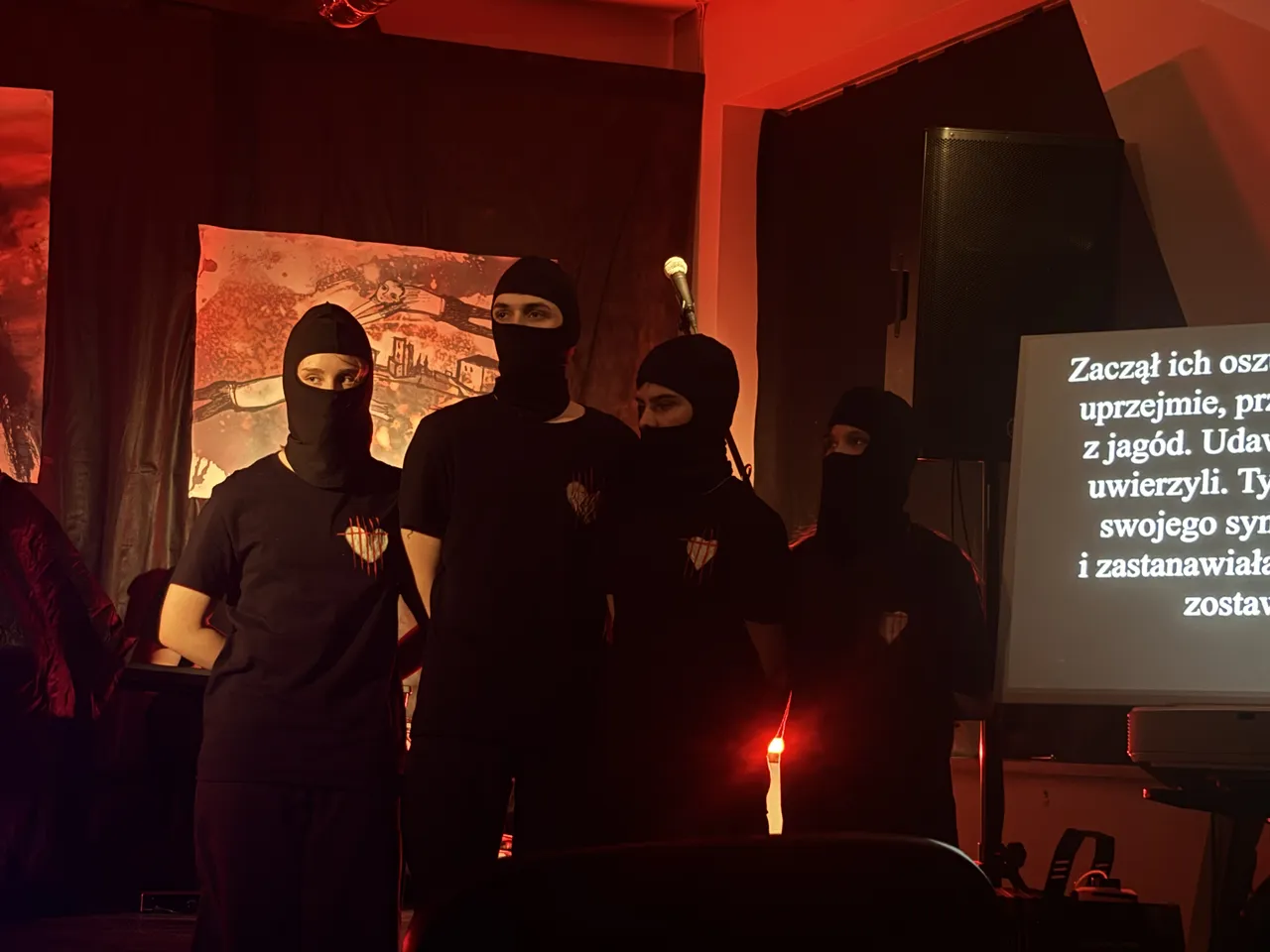

In the play My Mother in Prison, former actors of the Hrodna Drama Theater, who were forced to leave Belarus after the 2020 protests, perform alongside colleagues from the Old Vilnius Theater. The production is based on Volha Vialichka’s book From 2 to 15: My Mother in Prison. Students from the theatrical school Razam also participate, some of whom are children of political prisoners.

At the very beginning of the play, a teenager cries out, “World, hear us!” and the horrific stories of families deemed enemies of the people during Stalin’s era unfold one after another. One woman recounts how her children were taken to an orphanage. Another story tells of a mother who lost her mind after being separated from her young son, who subsequently died. Conditions in the camps for children were appalling; some children even unlearned how to cry, and not all survived.

The play features not only the memories of parents but also of the children who grew up in orphanages. Some began to feel ashamed of their parents as schoolchildren and even resented them, “because Grandpa Stalin is never wrong.” Other children wrote letters to Stalin, trying to explain that their parents were innocent. This part of the play concludes with the children’s repeated refrain: “May this never happen again! Never again, never again!”

Yet unpunished crimes continue to recur in the 2020s.

“Over the past years of my work, I realized that children of the repressed during the Soviet era and today’s children of political prisoners are very similar,” Volha Vialichka writes in her book. “I found only two differences: Belarusian children have a chance to see their parents alive, and I haven’t heard any of them say that other children teased them because their mom or dad is now in prison.”

After reading the memoirs of women who survived the Gulag, Vialichka understood that she needed to document the stories of the children she worked with: “Since 2020, not much time has passed; we still need to realize what happened to our society and this time work on correcting mistakes. I sincerely hope we do not turn this page the way the page of Soviet repression was turned,” she writes.

The director of the play embodies this idea literally, without pausing between the two historical periods of repression. After the words “May this never happen again,” a small boy approaches the microphone and says: “In Belarus, we have a disaster: all the good people are in prison, and the rest are very afraid.”

In My Mother in Prison, the voices of children tell the recent history of Belarus in almost stark black-and-white terms. The main characters are clear: parents and the dark villains. As the psychologist Volha Vialichka writes in her book, children understand that their parents have done nothing wrong—they are imprisoned solely for their political beliefs. Children explain about their parents: “They went to marches because they wanted a better life for us.”

The word “injustice” is repeatedly voiced by children whose parents are imprisoned. This sense of injustice is a key factor shaping their developing personalities, Vialichka notes. Both children and adults begin to doubt whether good ultimately overcomes evil, and this affects many aspects of life.

In the play, children recount what happened to them: how authorities came for their parents, how their mother was released, and what they felt during arrests and searches. They speak directly into the microphone. Although there is little traditional acting, the performance is layered, because the sheer weight of these stories leaves no room for dramatization. When the text becomes almost unbearable, a harsh mechanical sound fills the stage. At times, songs are performed—songs of despair, about prison walls or the black bulls of Mikhalko, and songs of hope, about a mother from Navibend.

Children also describe their dreams. In these dreams, strong winds carry their mother away, people in black appear, and they confront demons. In a normal environment, around 30% of children have anxious dreams, but under extreme stress, the hardest part is surviving the night. Vialichka explains: “Imagination creates terrifying monsters that escape precisely in dreams… Each of us has places we return to in such dreams, and there is no way to avoid them.” Psychotherapy aims to work through these dreams using conversation and art therapy, guiding them toward positive resolution.

During therapy sessions, children of political prisoners invent stories in which they articulate and work through their emotions, feelings, dreams, and desires. Their tales are unique: some are filled with hope that bad people can become good, that the villain will not return, and that injustice has been corrected. Others end badly, as the main character continues committing crimes with no consequences.

At the conclusion of the play, children voice their wishes: that their mother be released in March or granted home-based treatment (which the child calls happiness), that there exists a magical remote control to mute terrible people, and that they can visit Belarus to see their grandparents.

“What will remain when it’s all over? Only love…” the actors sing at the end. “Only love” are the final words of the entire performance. Mainly performed by children, My Mother in Prison resembles a psychotherapy session, leaving open the question of who benefits more—the adult audience or the children performing.

Svetlana Alexievich, in her preface to the book, calls children of political prisoners “fearless and honest witnesses.” Vialichka concludes her book with advice: “Help a child develop critical thinking.” The main takeaway from both the book and the play is clear: contemporary children, even at a young age, understand causes and consequences in a way that children under Stalin could not, offering hope that this page of history will not be turned over again.

Original article: reform.news