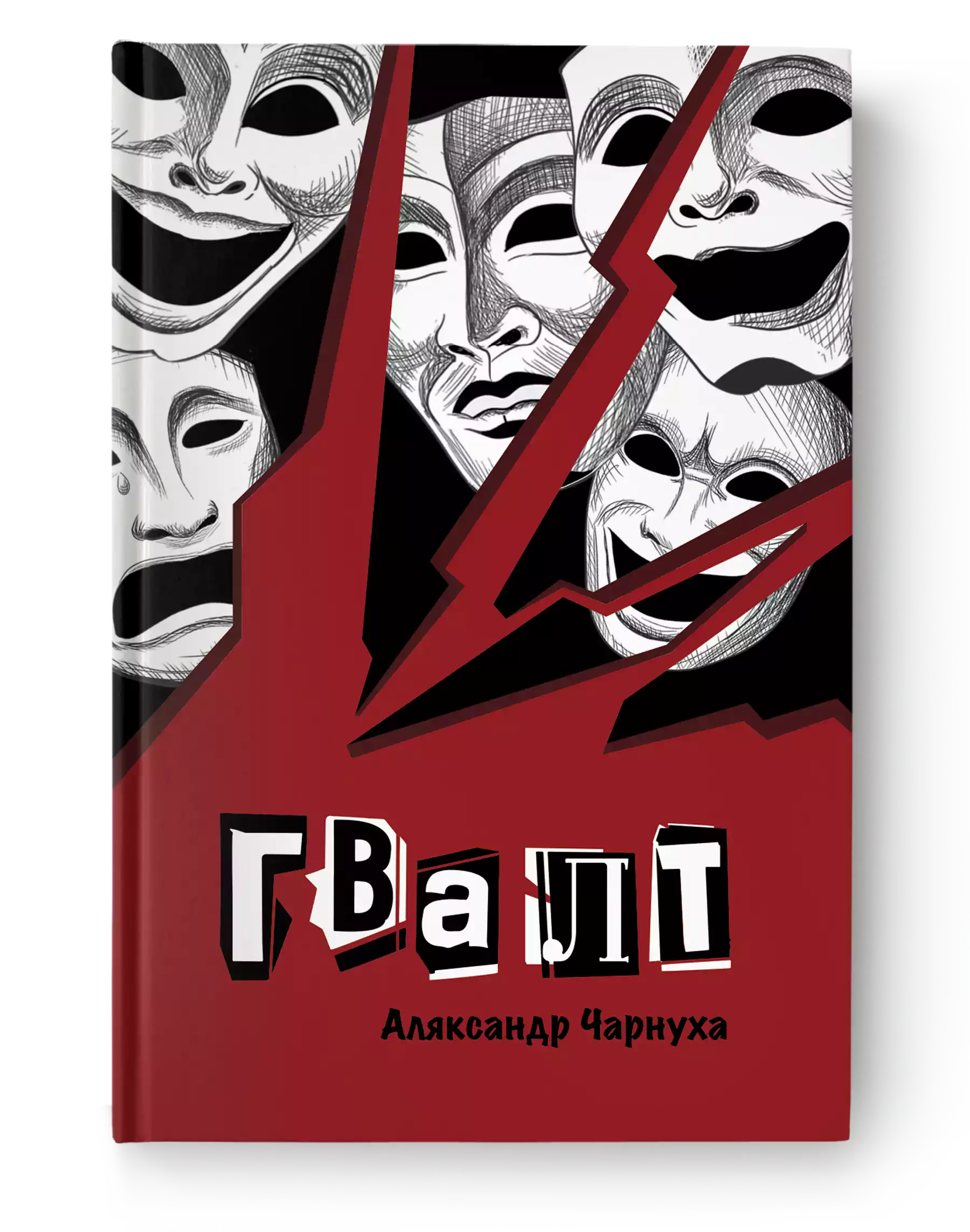

As the title suggests, Aliaksandr Charnukha’s book is about violence. However, the distinctive feature of these ten stories, written over two years in Warsaw, is the metaphorical nature of the portrayal of this violence.

In fact, these are ten parables, behind whose plots real events of recent years can be traced—events that, for us Belarusians, were difficult to escape. Violence in the book is depicted both on the state level, for example in the story “Globster,” where the Black Nothing appears on the Shklow beach, described by propagandists as boundless and unique (how can one not recall “dictatorship is our brand” here), and on the scale of a village, town, hospital, family, or prison.

Violence against language is one of the most striking plots, in which the “dead language” becomes almost a totemic object. Other stories address online counseling, the rape and punishment of a thirteen-year-old girl in Somalia, and even the work of political prisoners on an onion plantation, a plot inspired by an investigation from reform.news—though the goal of the plantation is different, and it is not the onions that become significant.

In other words, each story is brought to life by some kind of trauma. Yet the reader experiences it anew through the author’s perspective, no longer literally. The author seems to imprint concise fragments of tragic events into the book, which, unfortunately, do not lead to any liberating catharsis but do invite reconsideration. From this vantage, one can view those events from a metaphysical distance.

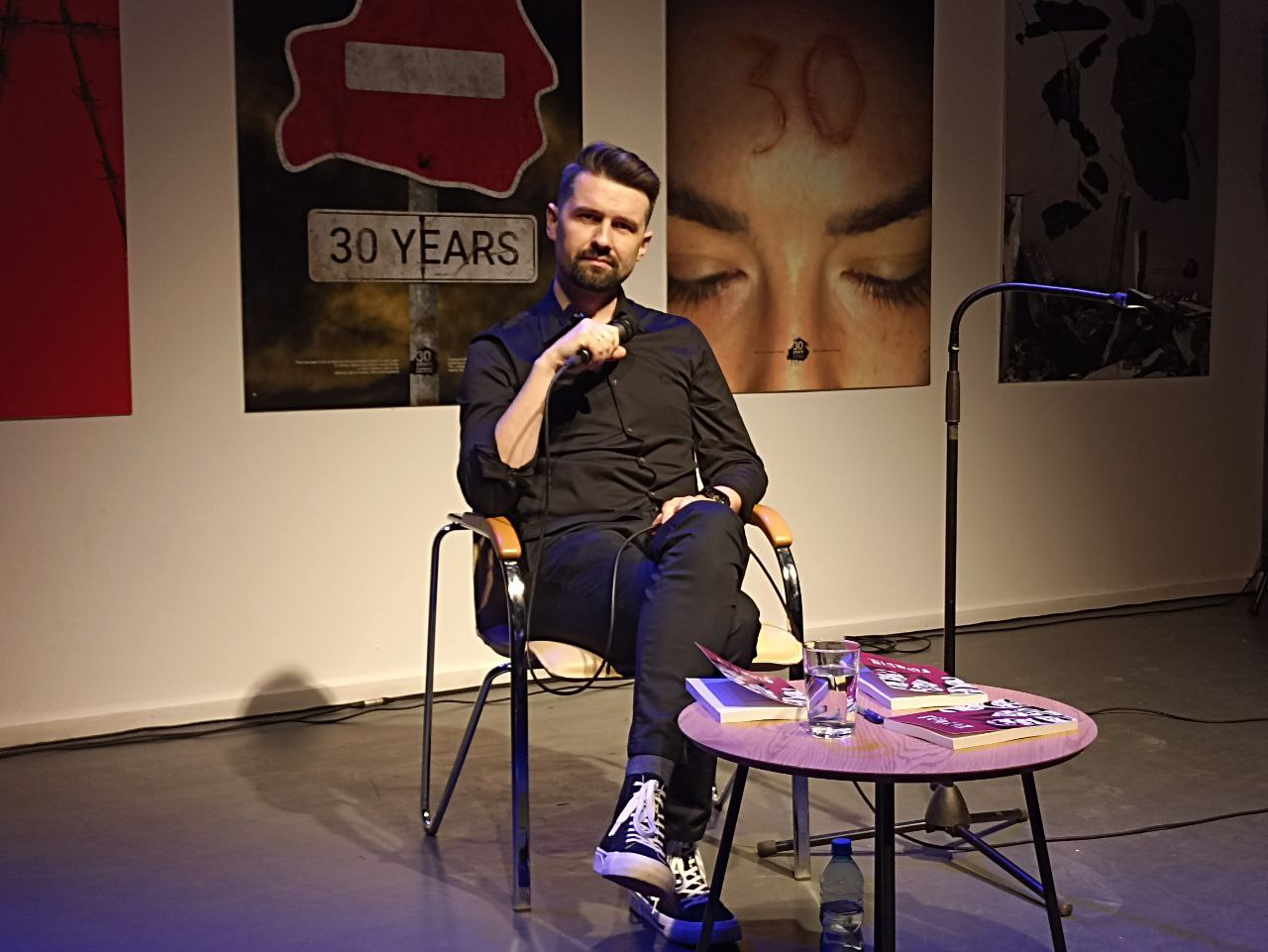

At the discussion, Aliaksandr Charnukha mentioned that one of the stories, most closely tied to a local context, “Uncle and Aunt Sat…”, was translated into English. As an experiment, it was read by an English-speaking person, and the result was not only understandable but also engaging. “All of these plots can exist in a global context,” Charnukha concluded at the presentation.

And one more conclusion that emerges after reading this book is that the boundary between real and surreal plots is rather blurred. Even in Charnukha’s previous book, “Pigs,” the real-life (according to the author) plots appeared entirely surreal. Incidentally, the first story in “Violence” serves as an afterword to the novel “Pigs”—the story of a dead official who is exhumed and made to speak before people. And it works!

The new book, the author explained at the presentation, is about the multidimensional nature of violence and its various shades. Here, victims are simultaneously perpetrators, because violence does not always come from one side. The stories explore both psychological and physical violence. Some narratives draw on personal experiences, for example, the illness of the author’s mother. Some events were covered in the media. But only in “Kotikі” does hope survive, he said, emphasizing in response to a question that violence is part of human nature and will never disappear.

Yet—and this is an important conclusion of the book—violence should be kept within certain limits. In Belarus, this is hardly achieved, nor is it attempted. That is why the book turned out tragic, with the endings of almost all stories left open.

The illustrations for the book were created by the author’s wife, Taisia Charnukha.

Original article: reform.news